The Deep Green Resistance Book

Strategy to Save the Planet

Some tactics can be carried out underground—like general liberation organizing and propaganda—but are more effective aboveground. Where open speech is dangerous, these types of tactics may move underground to adapt to circumstances. The African National Congress, in its struggle for basic human rights, should have been allowed to work aboveground, but that simply wasn’t possible in repressive apartheid South Africa.

And then there are tactics that are only appropriate for the underground, obligate underground operations that depend on secrecy and security. Escape lines and safehouses for persecuted persons and resistance fugitives are example of those operations. There’s a reason it’s called the “underground” railroad—it’s not transferable to the aboveground, because the entire operation is completely dependent on secrecy. Clandestine intelligence gathering is another case; the French Resistance didn’t gather enemy secrets by walking up to the nearest SS office and asking for a list of their troop deployments.

Some tactics are almost always limited to the underground:

As operational categories, intelligence and escape are pretty clear, and few people looking at historical struggles will deny the importance of gathering information or aiding people to escape persecution. Of course, some abolitionists in the antebellum US didn’t support the Underground Railroad. And many Jewish authorities tried to make German Jews cooperate with registration and population control measures. In hindsight, it’s clear to us that these were huge strategic and moral mistakes, but at the time it may only have been clear to the particularly perceptive and farsighted.

Sabotage and attacks on materiel are overlapping tactics. Oftentimes, sabotage is more subtle; for example, machinery may be disabled without being recognized as sabotage. Attacks on materiel are often more overt efforts to destroy and disable the adversary’s equipment and supplies. In any case, they form an inclusive continuum, with sabotage on the more clandestine end of the scale.

It’s true that harm can be caused through sabotage, and that sabotage can be a form of violence. But allowing a machine to operate can also be more violent than sabotaging it. Think of a drift net. How many living creatures does a drift net kill as it passes through the ocean, regardless of whether it’s being used for fishing or not? Destroying a drift net—or sabotaging a boat so that a drift net cannot be deployed—would save countless lives. Sabotaging a drift net is clearly a nonviolent act. However, you could argue conversely that not sabotaging a drift net (provided you had the means and opportunity) is a profoundly violent act—indeed, violent not just for individual creatures, but violent on a massive, ecological scale. The drift net is an obvious example, but we could make a similar (if longer and more roundabout) argument for most any industrial machinery.

You’re opposed to violence? So where’s your monkey wrench?

Sabotage is not categorically violent, but the next few underground categories may involve violence on the part of resisters. Attacks on troops, intimidation, assassination, and the like have been used to great effect by a great many resistance movements in history. From the assassination of SS officers by escaping concentration camp inmates to the killing of slave owners by revolting slaves to the assassination of British torturers by Michael Collins’s Twelve Apostles, the selective use of violence has been essential for victory in a great many resistance and liberation struggles.

Attacks on troops are common where a politically conscious population lives under overt military occupation. In these situations, there is often little distinction between uniformed militaries, police, and government paramilitaries (like the Black and Tans or the miliciens). The violence may be secondary. Sometimes the resistance members are trying to capture equipment, documents, or intelligence; how many guerrillas have gotten started by killing occupying soldiers to get guns? Sometimes the attack is intended to force the enemy to increase its defensive garrisons or pull back to more defended positions and abandon remote or outlying areas. Sometimes the point is to demonstrate the strength or capabilities of the resistance to the population and the occupier. Sometimes the point is actually to kill enemy soldiers and deplete the occupying force. Sometimes the troops are just sentries or guards, and the primary target is an enemy building or facility.

Of course, for these attacks to happen successfully, they must follow the basic rules of asymmetric conflict and general good strategy. When raiding police stations for guns, the IRA chose remote, poorly guarded sites. Guerrillas like to go after locations with only one or two sentries, and any attack on those small sites forces the occupier to make tough choices: abandon an outpost because it can’t be adequately defended or increase security by doubling the number of guards. Either benefits the resistance and saps the resources of the occupier.

And although in industrial conflicts it’s often true that destroying materiel and disrupting logistics can be very effective, that’s sometimes not enough. Take American involvement in the Vietnam War. The American cost in terms of materiel was enormous—in modern dollars, the war cost close to $600 billion. But it wasn’t the cost of replacing helicopters or fuelling convoys that turned US sentiment against the war. It was the growing stream of American bodies being flown home in coffins.

There’s a world of difference—socially, organizationally, psychologically—between fighting the occupation of a foreign government and the occupation of a domestic one. There’s something about the psychology of resistance that makes it easier for people to unite against a foreign enemy. Most people make no distinction between the people living in their country and the government of that country, which is why the news will say “America pulls out of climate talks” when they are talking about the US government. This psychology is why millions of Vietnamese people took up arms against the American invasion, but only a handful of Americans took up arms against that invasion (some of them being soldiers who fragged their officers, and some of them being groups like the Weather Underground who went out of their way not to injure the people who were burning Vietnamese peasants alive by the tens of thousands). This psychology explains why some of the patriots who fought in the French Resistance went on to torture people to repress the Algerian Resistance. And it explains why most Germans didn’t even support theoretical resistance against Hitler a decade after the war.

This doesn’t bode well for resistance in the minority world, where the rich and powerful minority live. People in poorer countries may be able to rally against foreign corporations and colonial dictatorships, but those in the center of empire contend with power structures that most people consider natural, familiar, even friendly. But these domestic institutions of power—be they corporate or governmental—are just as foreign, and just as destructive, as an invading army. They may be based in the same geographic region as we are, but they are just as alien as if they were run by robots or little green men.

Intimidation is another tactic related to violence that is usually conducted underground. This tactic is used by the “Gulabi Gang” (also called the Pink Sari Gang) of Uttar Pradesh, a state in India.4 Leader Sampat Pal Devi calls it “a gang for justice.” The Gulabi Gang formed as a response to deeply entrenched and violent patriarchy (especially domestic and sexual violence) and caste-based discrimination. The members use a variety of tactics to fight for women’s rights, but their “vigilante violence” has gained global attention. With over 500 members, they can exert considerable force. They’ve stopped child marriages. They’ve beaten up men who perpetrate domestic violence. The gang forced the police to register crimes against Untouchables by slapping police officers until they complied. They’ve hijacked trucks full of food that were going to be sold for a profit by corrupt officials. Their hundreds of members practice self-defense with the lathi (a traditional Indian stick or staff weapon). It’s no surprise their ranks are growing.

Many of these examples tread the boundary of our aboveground-underground distinction. When struggling against systems of patriarchy that have closely allied themselves with governments and police (which is to say, virtually all systems of patriarchy), women’s groups that have been forced to use violence or the threat of violence may have to operate in a clandestine fashion at least some of the time. At the same time, the effects of their self-defense must be prominent and publicized. Killing a rapist or abuser has the obvious benefit of stopping any future abuses by that individual. But the larger beneficial effect is to intimidate other would-be abusers—to turn the tables and prevent other incidents of rape or abuse by making the consequences for perpetrators known. The Gulabi Gang is so popular and effective in part because they openly defy abuses of male power, so the effect on both men and women is very large. Their aboveground defiance rallies more support than they could by causing abusive men to die in a series of mysterious accidents. The Black Panthers were similarly popular because they publically defied the violent oppression meted out by police on a daily basis. And by openly bearing arms, they were able to intimidate the police (and other people, like drug dealers) into reducing their abuses.

There are limits to the use of intimidation on those in power. The most powerful people are the most physically isolated—they might have bodyguards or live in gated houses. They have far more coercive force at their fingertips than any resistance movement. For that reason, resistance groups have historically used intimidation primarily on low-level functionaries and collaborators who give information to those in power when asked or who cooperate with them in a more limited way.

It’s important to acknowledge the distinction between intimidation and terrorism. Terrorism consists of violent attacks on civilians. Resistance intimidation directly targets those responsible for oppressive and exploitative acts and power structures, and lets those people know that there are consequences for their actions. The reason it gets people so riled up is because it involves violence (or the threat of violence) going up the hierarchy. But resistance intimidation is ultimately, of course, an attempt to reduce violence. Groups like the Gulabi Gang beat abusive men instead of just killing them. There’s a reasonable escalation that gives men a chance to stop their wrongdoing and also makes the consequences for further wrongdoing clear. Rape and domestic abuse are terrorism; they’re senseless and unprovoked acts of violence against unarmed civilians, designed to threaten and terrorize women (and men) into compliance. The intimidation of rapists or domestic abusers is one tactic that can be used to stop their violence while employing the minimum amount of violence possible.

No resistance movement wants to engage in needless cycles of violence and retribution with those in power. But a refusal to employ violent tactics when they are appropriate will very likely lead to more violence. Many abolitionists did not support John Brown because they considered his plan for a defensive liberation struggle to be too violent—but Brown’s failure led inevitably to a lengthy and gruesome Civil War (as well as continued years of bloody slavery), a consequence that was orders of magnitude more violent than Brown’s intended plan.

This leads us to the last major underground tactic: assassination.

In talking about assassination (or any attack on humans) in the context of resistance, two key questions must be asked. First, is the act strategically beneficial, that is, would assassination further the strategy of the group? Second, is the act morally just, given the person in question? (The issue of justice is necessarily particular to the target; it’s assumed that the broader strategy incorporates aims to increase justice.)

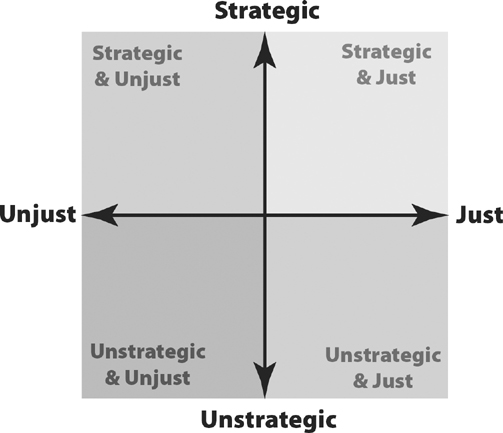

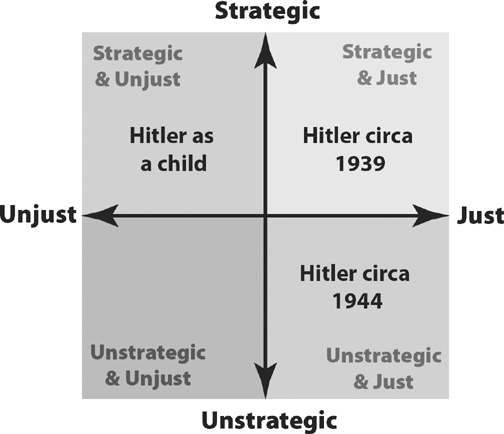

As is shown on my two-by-two grid of all combinations, an assassination may be strategic and just, it may be strategic and unjust, it may be unstrategic but just, or it may be both unstrategic and unjust. Obviously, any action in the last category would be out of the question. Any action in the strategic and just category could be a good bet for an armed resistance movement. The other two categories are where things get complex.

Figure 13-3

Hitler exemplified a number of different strategy vs. justice combinations at different points in time. It’s a common moral quandary to ask whether it would be a good idea to go back in time and kill Hitler as a child, provided time travel were possible. There’s a good bet that this would have averted World War II and the Holocaust, which would have been a good thing, so put a check mark in the “strategic” column. The problem is that most people would consider it unjust to murder an innocent child who had yet to commit any crimes, so it would be difficult to call that action just in the immediate sense.

Once Hitler had risen to power in the late 1930s, though, his aim was clear, as he had already been whipping up hate and expanding his control of Nazi Germany. At that point, it would have been both strategic and just to assassinate him. Indeed, elements in the Wehrmacht (army) and the Abwehr (intelligence) considered it, because they knew what Hitler was planning to do. Unfortunately, they were indecisive, and did not commit to the plan. Hitler soon began invading Germany’s neighbors, and as his popularity soared, the assassination plan was shelved. It was years before inside elements would actually stage an assassination attempt.

Figure 13-4

That famous attempt took place—and failed—on July 20, 1944.5What’s interesting is that the Allies were also considering an attempt on Hitler’s life, which they called Operation Foxley. They knew that Hitler routinely went on walks alone in a remote area, and devised a plan to parachute in two operatives dressed as German officers, one of them a sniper, who would lay in wait and assassinate Hitler when he walked by. The plan was never enacted because of internal controversy. Many in the SOE and British government believed that Hitler was a poor strategist, a maniac whose overreach would be his downfall. If he were assassinated, they believed, his replacement (likely Himmler) would be a more competent leader, and this would draw out the war and increase Allied losses. In the opinion of the Allies it was unquestionably just to kill Hitler, but no longer strategically beneficial.

There is no shortage of situations where assassination would have been just, but of questionable strategic value. Resistance groups pondering assassination have many questions to ask themselves in deciding whether they are being strategic or not. What is the value of this potential target to the enemy? Is this an exceptional person or does his or her influence come from his or her role in the organization? Who would replace this person, and would that person be better or worse for the struggle? Will it make any difference on an organizational scale or is the potential target simply an interchangeable cog? Uniquely valuable individuals make uniquely valuable targets for assassination by resistance groups.

Of course, in a military context (and this overlaps with attacks on troops), snipers routinely target officers over enlisted soldiers. In theory, officers or enlisted soldiers are standardized and replaceable, but, in practice, officers constitute more valuable targets. There’s a difference between theoretical and practical equivalence; there might be other officers to replace an assassinated one, but the replacement might not arrive in a timely manner nor would he have the experience of his predecessor (experience being a key reason that Michael Collins assassinated intelligence officers). That said, snipers don’t just target officers. Snipers target any enemy soldiers available, because war is essentially about destroying the other side’s ability to wage war.

The benefits must also outweigh costs or side effects. Resistance members may be captured or killed in the attempt. Assassination also provokes a major response—and major reprisals—because it is a direct attack on those in power. When SS boss Reinhard Heydrich (“the butcher of Prague”) was assassinated in 1942, the Nazis massacred more than 1,000 Czech people in response. In Canada, martial law (via the War Measures Act) has only ever been declared three times—during WWI and WWII, and again after the assassination of the Quebec Vice Premier of Quebec by the Front de Libération du Québec. Remember, aboveground allies may bear the brunt of reprisals for assassinations, and those reprisals can range from martial law and police crackdowns to mass arrests or even executions.

There’s an important distinction to be made between assassination as an ideological tactic versus as a military tactic. As a military tactic, employed by countless snipers in the history of war, assassination decisively weakens the adversary by killing people with important experience or talents, weakening the entire organization. Assassination as an ideological tactic—attacking or killing prominent figures because of ideological disagreements—almost always goes sour, and quickly. There are few more effective ways to create martyrs and trigger cycles of violence without actually accomplishing anything decisive. The assassination of Michael Collins, for example, by his former allies led only to bloody civil war.